Car crashes are relatively rare – which is great – but unfortunately, we still have to deal with them, no matter how much technology advances. About 9 people are injured in vehicle crashes for every 100 million miles traveled according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Here’s the thing about computer-based cars: They’re not amazing at predicting rare events. Because the computers analyze past events they look for the most common issues and protect from them, but they don’t always anticipate the unlikely events.

“Accidents are going to be rare anyway, and models tend to miss rare events because they just don’t occur frequently enough,” says Tristan Glatard, a professor of computer science at Concordia University working to build models that might predict car crashes before they happen. “It’s like finding a needle in a haystack.”

Some truly helpful things could happen if we were to find that needle in the haystack. If we can manage to transform streets and roads into streams of data, we might be able to predict where accidents will occur. This has the potential to allow emergency responders to come to the scene of the accident faster than normal and will also allow the government to find problematic roads and work on fixing them.

We all know that one road near where we live that seems like it always has potholes or constantly has accidents in a certain area during the winter, and this has the potential to fix that!

Okay, it’s not exactly predicting the future, but it’s close. Even though it’s hard and often expensive and complicated, cities, researchers, and the federal Department of Transportation are working to fix our roads.

In May, a team of researchers with UCLA and UCI published a paper suggesting that places in California might be able to use data from Waze to cut emergency response times. Because Waze is crowdsourced they can receive notifications about accidents faster than if someone called it in to an emergency responder.

When using the Waze App, users can easily mark if there is a police officer, accident, or other obstacle in the road. This information is all stored on Google servers (Google owns Waze) and the real time information can help responders get to accident sites efficiently.

By comparing the data from the Google-owned service with crash data from the California Highway Patrol, the researchers concluded that Waze users notify the app of crashes an average of 2 minutes and 41 seconds before anyone alerts law enforcement.

The three minutes of lead time might not always be the difference between life and death but “if these methods can cut the response time down by between 20 to 60 percent, then it’s going to have the positive clinical impact,” says Sean Young, a professor of medicine at UCLA and UCI. “It’s generally agreed upon that the faster you get into the emergency room, the better the clinical outcomes will be.”

Last year, the Department of Transportation’s Volpe Center wrapped up its own analysis of six months of Waze and accident report data from Maryland and found its researchers could build a computer model from the crowdsourced info that closely followed the crashes reported to the police. The crowdsourced data actually had some advantages over the official police crash tallies because users reported crashes that weren’t major enough to be reported, but were major enough to cause traffic slowdowns, potentially making it a more accurate statistic than the government’s.

The DOT is funding additional research with cities that might use the data. In Tennessee, government researchers are working with the Highway Patrol to incorporate Waze data into the state’s crash-prediction model, with the end goal of making it accurate down to an hour inside of a one-square-mile grid, instead of the current four hours within a 42-square-mile grid.

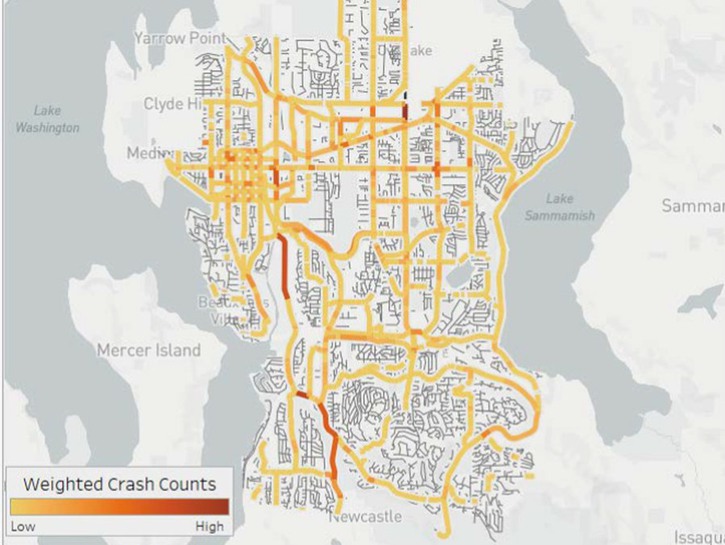

In Bellevue, Washington, the DOT has helped to build an interactive dashboard that officials can use to identify crash patterns and risks. If a bunch of crashes are happening in the same section of roadway, “then the heatmap starts glowing,” says Franz Loewenherz, a Bellevue transportation planner. The city might then start collecting data from local traffic cameras to look for causes.

Bellevue is a strong test for this kind of data experiment because it’s for being very good at collecting and coordinating data from police crash reports and 911 calls to tweak its transportation. The DOT can use Bellevue to test how close the crowdsourced traffic data is to what’s actually happening on the ground.

It will take a lot of work before these sorts of traffic data experiments become popularized, partly because few places are like Bellevue. “You have to have a lot of data, and diverse types of data, and then be able to analyze it for it to be actionable instead of just piling up,” says Christopher Cherry, an engineering professor at the University of Tennessee who recently completed a study of how traffic data could be used to improve road safety. The data itself is useful but to predict the risk of crashes, and to prevent them, you need to know where crashes are happening, what the roads in question are like, and how those roads perform under different weather conditions. And then you have to link all those datasets up and help them talk to each other. Obviously this is not something that is easily done, but the potential of this technology could lead to more investment in this type of research.

The reason that Google traffic data can’t be subbed for 911 calls is that there are still plenty of false positives when traffic data identifies a crash that isn’t there, or isn’t serious enough to warrant medical attention. “If you use Waze data as the gold standard, and any time a Waze user reports a car crash you alert police departments, then you’re diverting them from all kinds of other resources needed for crime, for public health and safety,” Young says.

Glatard and his team at Concordia recently released a paper suggesting they could combine three datasets—on the city’s road networks, crashes, weather to predict where crashes might happen with 85 percent accuracy. This does, however, mean that one out of every eight crashes it predicts never end up happening. Eventually, he’d like to see city authorities use this kind of info to route drivers around streets that get especially dangerous when it snows.

With technology progressing and crowdsourced navigation apps becoming more and more popular, we have the potential to change the emergency response system as we know it and can save the lives of many people each year due to decreased response times and more accurate reads of roads so that people can reroute to avoid dangerous conditions.

- The Best McDonald’s Happy Meal Toys of All Time

- ‘Cheers’: How Bart Simpson Met Sideshow Bob Years Before ‘The Simpsons’

- ‘Family Guy’s Seth MacFarlane Praises Adam West as a ‘Joy to Work With’

- Christopher Reeve’s Children Reveal His Proudest Role…and It’s Not Superman

- Snoop Dogg’s Old School Car Collection is Perfection Perfected